They spy: Christine Granville and Francis Cammaerts

The life expectancy of a WW II spy was not long, but Christine Granville flashed across the sky with particular brightness. Of the two books I read about her, The Spy Who Loved by Claire Mulley was by far the better written and researched. Published in 2012, the author had access to previously classified documents. Claire Mulley explicates her book title: Christine loved life, men, adventure, independence and Poland.

Christine, by Madeleine Masson was scrubbed clean under orders from a group of friends and admirers that banded together to protect Christine’s reputation after her death in 1952 . Masson was herself an agent in France and she had, briefly, met Christine.

Christine was born Krystyna Skarbek in 1908 in Warsaw, the daughter of a Catholic count and a wealthy Jewish woman. She grew up riding, skiing, hiking and being bored and mischievous at school, if setting a priest’s robes on fire in order to make mass go faster could be called mischievous. Later in her life she was described as being “a loner and a law unto herself” (Vera Atkins) and as having “an almost pathological tendency to take risks” (Owen O’Malley.) Today she probably would have been medicated.

It was for Poland that she began her career as a spy, and entirely of her own initiative. In Hungary after Hitler invaded Poland, she made contact with the seminal Polish resistance, which was trying to get British propaganda into Poland. All borders were closely guarded except for where the Tatra Mountains separated the two countries. The mountains were so treacherous that it seemed a waste of resources to patrol them. Jan Marusarz, a pre-war Olympic skiing star was doing courier work across the Tatras when Christine persuaded him to let her go with him. It was the worst winter in living memory but they made it across.

One document that Christine smuggled out of Poland was an early indication of Barbarossa, Hitler’s plan to invade Russia. This was the first inkling of Barbarossa to arrive on Churchill’s desk.

Christine had a magnetic personality. She had a magic touch with both people and animals. Once she was sniffed out by a German dog while hiding from a patrol. She put her arm around the dog and whispered to it. It lay down with her and wouldn’t go back to its handler. The dog became a mascot for that group of resisters.

At a patrol check, Christine was carrying a stack of propaganda material that would most certainly have gotten her shot. She flirted briefly with a German officer and then confessed that she had a parcel of black market tea that she didn’t want to be caught with. Could he take it through the patrol for her? The officer obliged and carried her contraband in his luggage, giving it to her on the other side.

Christine’s story is full of episodes like these, which I gather she thrived on. Me, I almost wet myself just writing about it.

It seems impossible to tell Christine’s story without bringing in Francis Cammaerts so here he comes. Of the books I read, A Pacifist at War by Roy Jenkins is disjointed by the use of long transcriptions from personal interviews with Cammaerts, but that is also its greatest value. They Came from the Sky by E.L. Cookridge is a good read. Cammaerts is one of three agents he profiles.

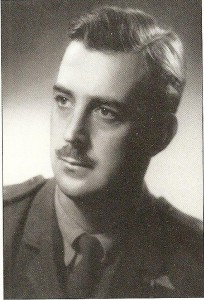

Francis was the son of a Belgian poet-laureate and an English Shakespearean actress. The family left Belgium at the start of World War I and Francis was born in 1916 in London. He began World War II as a pacifist, but when his brother Pieter was shot down and killed, he changed his mind about fighting. Francis, however, was not military material:

“Once you’d accepted the notion of discipline of an armed force you were bound to accept the possibility of stupid and ridiculous orders which you’d have to obey. . . I had no intention of getting into any branch of combat except one where if somebody gave me a silly order, I could write back and say ‘don’t be a bloody fool.’”

Francis was exactly what S.O.E. was looking for. He established the Jockey circuit in southeast France, overseeing a large area from Lyon in the north to the Mediterranean in the south and from the Rhône river to the maritime alps. A circuit was made up of cells of 10-15 people that were insulated from other cells. No one knew how to get a hold of Francis–who never spent more than three nights in any one place–but Francis knew how to contact anyone in his circuit.

Still only in his twenties, Francis was tall with huge feet. Liked and respected by the resistance, they called him “le Diablo Anglais” or sometimes “Grands Pieds.” He traversed his area over and over, dealing patiently with problems and situations as they came up.

Francis worked most closely with a wireless operator and a courier. One of the main activities of the S.O.E. agents were to locate suitable places for drops: the parachuting in of other agents and of canisters packed with weapons, ammunition, grenades, materials for making bombs, clothing, cigarettes, tea, chocolate, and money. Having found a potato field or clearing, the wireless operator sent the location coordinates in a coded message to S.O.E. headquarters in London. Dates and times were arranged during full moon periods and RAF ‘special duty flights” did the drops.

The dispersal of arms and ammunition had to be arranged and people had to be trained to use the weapons. Then there was the actual blowing up of things: trains, bridges, the Peugeot factory. The arrangements were clandestine and dangerous. Francis insisted that each person work out a “legitimate” reason for any resistance activity in case of being stopped by a patrol or worse, taken into custody. There were no written messages. It was a dangerous world. You could be arrested and interrogated if you happened to look right –as the British do–before crossing the street.

Besides sabotage, there was recruitment of new members, something that had to done delicately. There were agents coming and going that had to be briefed and for whom flights had to be arranged. Downed airmen had to be hidden and then gotten onto escape routes. The Germans patrolled the hospitals so finding doctors was tricky. All in a day’s work.

One of the most exciting and sad stories of resistance lore is that of the Vercors. A huge plateau rising up west of Grenoble, it was part of Francis’ territory. They met when Christine was parachuted in as his new courier. That’s my next story.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

Leave a Reply